Our History

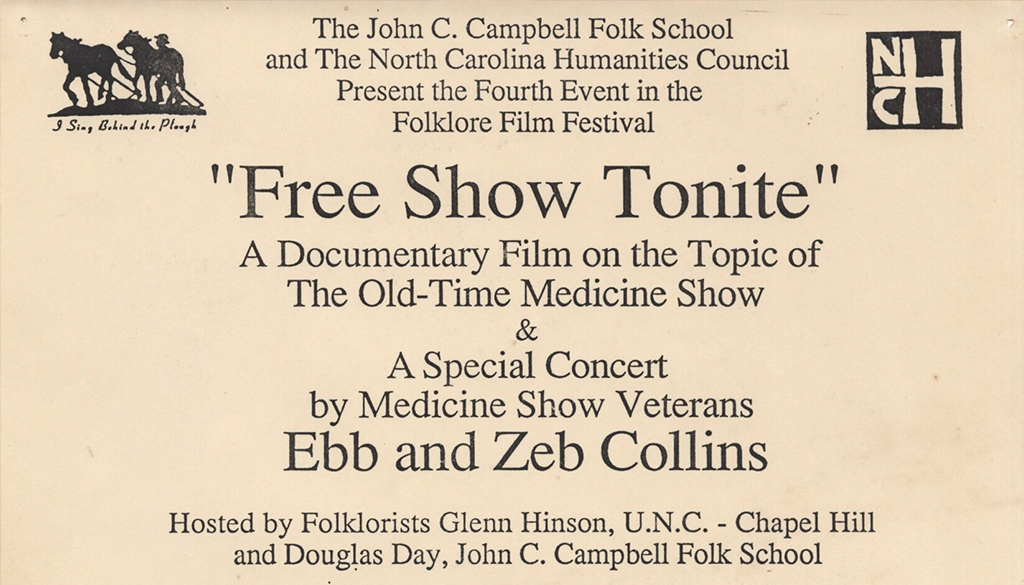

The folkehøjskole, “folk high school,” had long been a force in the rural life of Denmark. These “schools for life” helped transform the Danish countryside into a vibrant, creative force. The Campbells talked of establishing such a school in the rural southern United States.

The Folk School’s founding

John C. Campbell, born in Indiana and raised in Wisconsin, studied education and theology in New England. Like many other idealistic young people of his generation, he felt a calling to humanitarian work. At the turn of the century, the Southern Appalachian region was viewed as a fertile field for educational and social missions. With his new bride, Olive Dame of Massachusetts, John undertook a fact-finding survey of social conditions in the mountains in 1908–1909. The Campbells outfitted a wagon as a traveling home and studied mountain life from Georgia to West Virginia.

While John interviewed farmers about their agricultural practices, Olive collected ancient Appalachian ballads and studied the handicrafts of the mountain people. Both were hopeful that the quality of life could be improved by education, and in turn wanted to preserve and share with the rest of the world the wonderful crafts, techniques, and tools that the mountain people used in everyday life.

The folkehøjskole, “folk high school,” had long been a force in the rural life of Denmark. These “schools for life” helped transform the Danish countryside into a vibrant, creative force. The Campbells talked of establishing such a school in the rural southern United States.

After John died in 1919, Olive and her friend, Marguerite Butler, traveled to Europe and studied folk schools in Denmark, Sweden, and other countries. They returned to the U.S. full of purposeful energy and a determination to start such a school in Appalachia.

They realized, more than many reformers of the day, that they could not impose their ideas on the mountain people. They would need to develop a genuine collaboration. Several locations were under consideration for the experimental school. On an exploratory trip, Miss Butler discussed the idea with Fred O. Scroggs, Brasstown’s local storekeeper, and said she would be back in a few weeks to see if any interest had been shown. When she returned, it was to a meeting of over 200 people at the local church. The people of Cherokee and Clay counties pledged labor, building materials, and other support. The Scroggs family gave land.

In 1925, the Folk School began its work. Instruction at the Folk School has always been noncompetitive; there are no credits, no grades, no pitting of one individual against another. This method of teaching is what the Danes called “The Living Word.” Discussion and conversation, rather than reading and writing, are emphasized—and most instruction is hands-on.

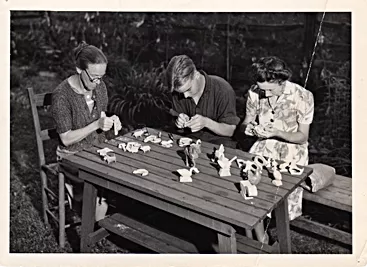

Brasstown Carvers

``Often `{`carving`}` has meant the sole source of a doctor's bill...or food for my children. I am happy that I have the gift of carving and that the Folk School has given me the opportunity to use it.``

This 1947 testimonial from Brasstown Carver Hope Brown helps express the stability that the carving cooperative brought to the Brasstown community. Our local folklore traces the beginning of the Brasstown Carvers to Mrs. Campbell, who witnessed a group of men on the porch of Fred O. Scroggs’ general store, “idly whittlin’” with their pocket knives. When no spare wood was available, these self-proclaimed sons of rest would carve into the bench on which they sat. In an effort to preserve his bench, Fred O. drove nails into the length of the bench, which persistent carvers worked around. Mrs. Campbell saw the potential skill and productivity in these men and provided them with blocks of wood and direction.

The Brasstown Carvers flourished under the leadership of Murrial Decker Martin, who was hired as the craft teacher in 1935. As an occupational therapist, Murray had experience teaching both weaving and carving. Murray’s designs of mad mules, geese, pigs, dogs, and other animals observed on the farm, have made the carvings nationally recognizable. Murray provided carvers from a radius of ten miles with blocks sawed out at the school’s wood shop. Carvers would walk to the school weekly to pick up blanks, drop off finished products, and meet with Murray and other carvers for informal critiques. This social setting was conducive to discussions about politics, local issues, farm practices, and topics of a greater scope, further uniting the community.

Murray’s leadership, as well as increasingly stressful economic conditions brought on by World War II, encouraged more women to take up carving. Traditionally wives would be involved in the sanding and finishing process, but, in the 1940s, it was quite common for women to hold their own as carvers. The supplemented income that carving brought to these farming families was enough incentive for anyone to be willing to learn the skill.

Prolific carvers became recognizable, such as Glenn and Hope Brown, John, Jack, and Ben Hall, Nolan Beaver, and Dot Reece.

A notable case of success brought on by carving is the Hensley family. Hayden and Bonnie Logan Hensley were early students and carvers at the Folk School. Their supplemental carving income allowed them to purchase a home which they referred to as “the house that carving built.” Although the economic benefits certainly motivated carvers, they stressed that they carved for the pure joy of it.

The tradition of the Brasstown Carvers is thoroughly alive today. Today’s Brasstown Carvers group includes Helen Gibson, Richard Carter, Angela Wynn, Carolyn Anderson, Edward Hall, and Terrence Fairies. Each carver produces work and then delivers it to the Folk School Craft Shop twice a month.

Interested in becoming a Brasstown Carver? Let's Talk!

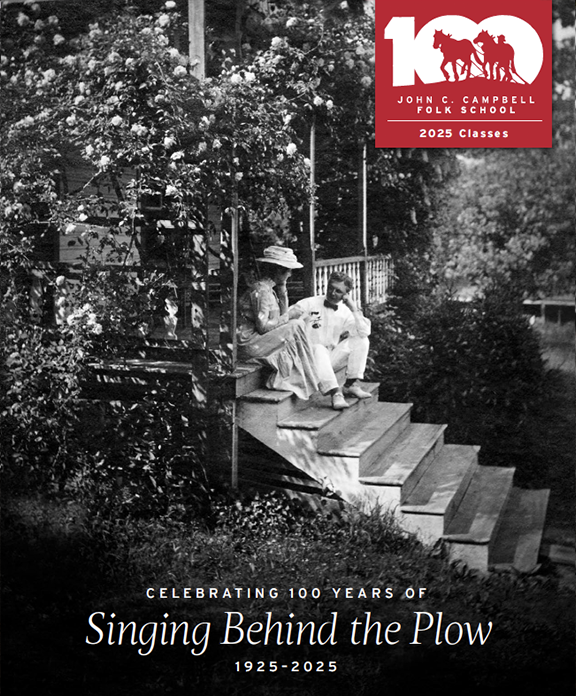

Doris Ulmann’s Craft Revival photographs

A photographer raised on the Upper West Side of New York City, Doris Ulmann later became one of the key image-makers associated with documenting the Craft Revival moment in the southern United States. Ulmann’s early success in the field of photography was evidenced by publication in medical journals, exhibitions, and her association with the Pictorial Photographers of America, an organization for artistic photography founded by Clarence White. Ulmann captured images of Alfred Einstein, Robert Frost, William Butler Yeats, and other notables in the medical and literary world before turning her lens on what she called “vanishing types.” During this period, she documented Mennonites, African Americans in the Gullah region of South Carolina, and people living in the mountains of Appalachia. Many of her later photographs were taken around Brasstown and feature important Folk School figures including founders Olive Dame Campbell and Marguerite Butler, instructor Louise L. Pitman, and a number of early Brasstown Carvers.

In the mid-1920s, Doris Ulmann began her photographic expeditions throughout Appalachia. With folk musician and ballad collector, John Jacob Niles as her travel companion and assistant, Ulmann spent her final seven years documenting daily life, work, and handcrafts in Appalachia. While Ulmann captured the aesthetic of the craftsman’s work-worn faces and hands, Niles collected ancient mountain ballads that were passed down from Scotch-Irish ancestors.

Ulmann was asked by Allen Eaton to provide documentary photographs which he would eventually include in his 1937 book, Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands. Working exclusively in North Carolina in 1933 and 1934 when she died, Ulmann considered Brasstown to be her home-base. While she spent much time photographing Appalachian settlement schools and regions rich with craft, such as Berea, Kentucky, and Hilton Pottery in Hickory, North Carolina, Ulmann had a special connection with Brasstown. Her photography of students and staff of the John C. Campbell Folk School and local craftspeople and musicians around Brasstown led her to form a very close friendship with Folk School founder, Olive Dame Campbell. In letters to Campbell, Ulmann confides in her as a friend and colleague and expresses her support of the Folk School. In a letter dated May 22, 1934, Ulmann writes, “If you only could know…how homesick we are for you!…The more we see of other places, the greater is our appreciation of you and your wonderful school and the beautiful influence which you have on the people in your school…and in your part of the mountains.”

Doris Ulmann died at the age of 52 in August of 1934. Her prolific photographs, many printed posthumously, can be found in collections nationwide. The Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection in the John C. Campbell Folk School Archives has over 200 prints, mostly of the Brasstown area.

from the Folk School’s History Center and Fain Archives

Read more about Doris Ulmann on Craft Revival, A Project of Hunter Library Digital Initiatives at Western Carolina University

Doris Ulmann Stories

More Stories from the Archives

Curious to learn more about the Folk School’s almost hundred-year-old history? Explore these stories that delve into our rich and diverse collection housed in the Fain Archives.