15 Feb What is a Folk School? An interview Dawn Murphy, Vice President of the Folk Education Association of America

For many of our students, John C. Campbell is their first experience with a folk school’s unique education model: small-sized, non-competitive classes with the end goal of personal enrichment. Based on the folkehøjskole of rural Denmark, folk schools emphasize process over product, foster communal spirit, and spark personal transformation. New schools adopting the folkehøjskole model are starting in rural Appalachia, Minnesota, and as far north as Alaska and Canada!

We’re delighted that Dawn Murphy, the Vice President of the Folk Education Association of America, will give three presentations about the history of folk schools and their resurgence in North America during our inaugural Roots of the Folk School week, March 5-11, 2023.

As a preview, Robert Grand, our Communications and Brand Manager, spoke to Dawn about the tried and true folk school model and its rising prominence today – almost a hundred years after John C. Campbell was founded. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

RG: Let’s start with the basics. For those unfamiliar, what is a folk school?

DM: When I get this question, I just laugh because everyone wants to know what a folk school is. I think the only definition you can put on it is, “It’s fuzzy.” It’s a term borrowed from mathematics: A “fuzzy set” is a group of numbers with common characteristics, but the group is time and context-dependent. Membership in a set will change as those elements change. Can you say that John C. Campbell is the quintessential folk school and everything you do fits perfectly within the folk education model? No, but it is a folk school fit for Brasstown, North Carolina, and in its current form, for the times we live in now.

I think there are some concrete characteristics among folk schools: mainly, providing education that is non-competitive, non-graded, non-compulsory, and consisting of mostly avocational opportunities.

What happens at a folk school, generally, is building community and connection. Folk schools are about people coming together, making concrete connections to themselves and to others in community and, ultimately, in society. That’s the awakening and the enlightenment you see described in many of our members’ mission statements.

We’ve had a folk school in the Alliance that specializes in teaching website development, and we have a folk school based around living room conversations. They can resemble many different things. You’ll see as many kinds of folk schools as you’ll find people willing to start one.

RG: Great point! It does feel like the more you try to hold on to a strict definition of “folk school,” the more you may lose sight of all that the format can make space for.

DM: When trying to define a folk school, there are those that want an answer, and there’s a whole spectrum of other people who pose it as a question, and there are all those in between. It’s complex because “folk” in this sense means “people” and we are all complex, adaptive beings.

From left to right: a painting class at the Duluth Folk School; a music class at the Alabama Folk School; knives made at the Palmer Folk School

RG: Exactly. When most people hear “folk school,” they think of Appalachian Mountain culture or Bob Dylan songs, but it’s not tied to either one of those things.

DM: The definition of “folk” we use originates from the Folk High School movement of Denmark: N.F.S. Grundtvig’s folk high school or the “School for Life.” Folk education and folk schooling promote learning of other people’s cultures without an elevation of your own above theirs, and that is baked into what folk education philosophy is about.

Fundamentally, the folk high schools in Denmark back in the 1800s were about the common farmer folk who were actively excluded from power within Denmark. Parts of Denmark had been taken away during a war, the elite in the country were adopting German ways and Latin education system, and the common folks’ ways of being were seen as not important. Basically, their culture was being dissolved, and folk education was a way of elevating the Danish culture and traditions to the status of others.

RG: Who are some of your members? I see they are scattered all over the country.

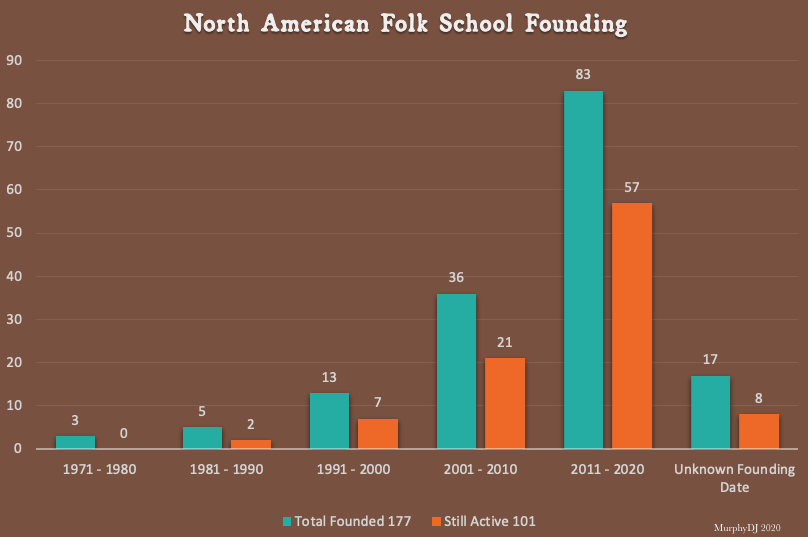

DM: We have around 97 members in approximately 28 states and three provinces in Canada. John C. Campbell is the oldest folk school in our membership and the youngest is a couple months old. In the late 1990s, there were probably 7 members. So from 2000 up to 2019, it was astounding; there was like an eight-fold increase in the number of organizations calling themselves “folk schools” in North America. The trend line was quite dramatic, as you can see in this graph:

In 2018, we had our first regional meet-up in Minnesota with about 25 folk schools, and I asked those who founded folk schools, “Why?” They said it was a feeling of being disconnected, of technology taking over their lives, of wanting to give back to their community and also to know about their community deeply. Wanting to be more connected to people and place and the history of that place––including the indigenous folks whose land they are on.

RG: How did you hear about folk schools?

DM: I learned about folk schools through John C. Campbell. A friend of mine from South Carolina, whom I taught to knit, was learning how to spin. She said, “Why don’t we go to the John C. Campbell Folk School?” and–I’m sure you hear this all time–but then I said, “What’s a folk school?” This was in 2003. I did a search on the internet and the other folk school that came up was Highlander, and there’s a lot written about them. When I connected cultural identity development with anti-oppression work, I was hooked.

Little did that person that I taught to knit know that that my life would take such a veering jaunt after a couple of years. For 10 years, essentially, I was looking at going to John C. Campbell, but I didn’t have enough money. I was working at community colleges, and I was in Southern California, so getting there was too much of a jump for me. But I started seeing more folk schools popping up during that time. I also wanted to do a Ph.D. but was tired of talking about community college education and decided to study the growing number of folk schools in North America. That’s when I called a phone number on a random website–I think this was 2013–and ended up talking to a young woman who had just started the Folk Education Association of America up again. Long story short, I came into it, we re-established non-profit status, I’m nearing the end of my doctoral study, and the work keeps going.

RG: How long has the Folk Education Alliance of America been around? How was it founded?

DM: The organization was founded in 1976 by a group of people who had experience with the Scandinavian Folk High Schools and, in particular, the Danish Folk High Schools. The two individuals that are identified as leading the founding group are Kay Parke and John Ramsay. They began writing to each other in early 1975 about what they called a “folk-college experience.” The original communication talks about providing an experience at Berea College or some other appropriate setting. This discussion turned into a discussion of a Folk-College Association, and in February 1976, a small group met at Berea College and agreed to form the association. By October of 1976, the group had elected its first slate of officers and held a strategy meeting with the aim of Incorporating as an Association in the state of Kentucky, while reaching across the US and Canada for its membership. Much of the initial work on organizing and communicating with the larger founding group came from and through Kay Parke and John Ramsay; however, Richard Drake, Loyal Jones, Loren Kramer, and Mary Hawley were also involved.

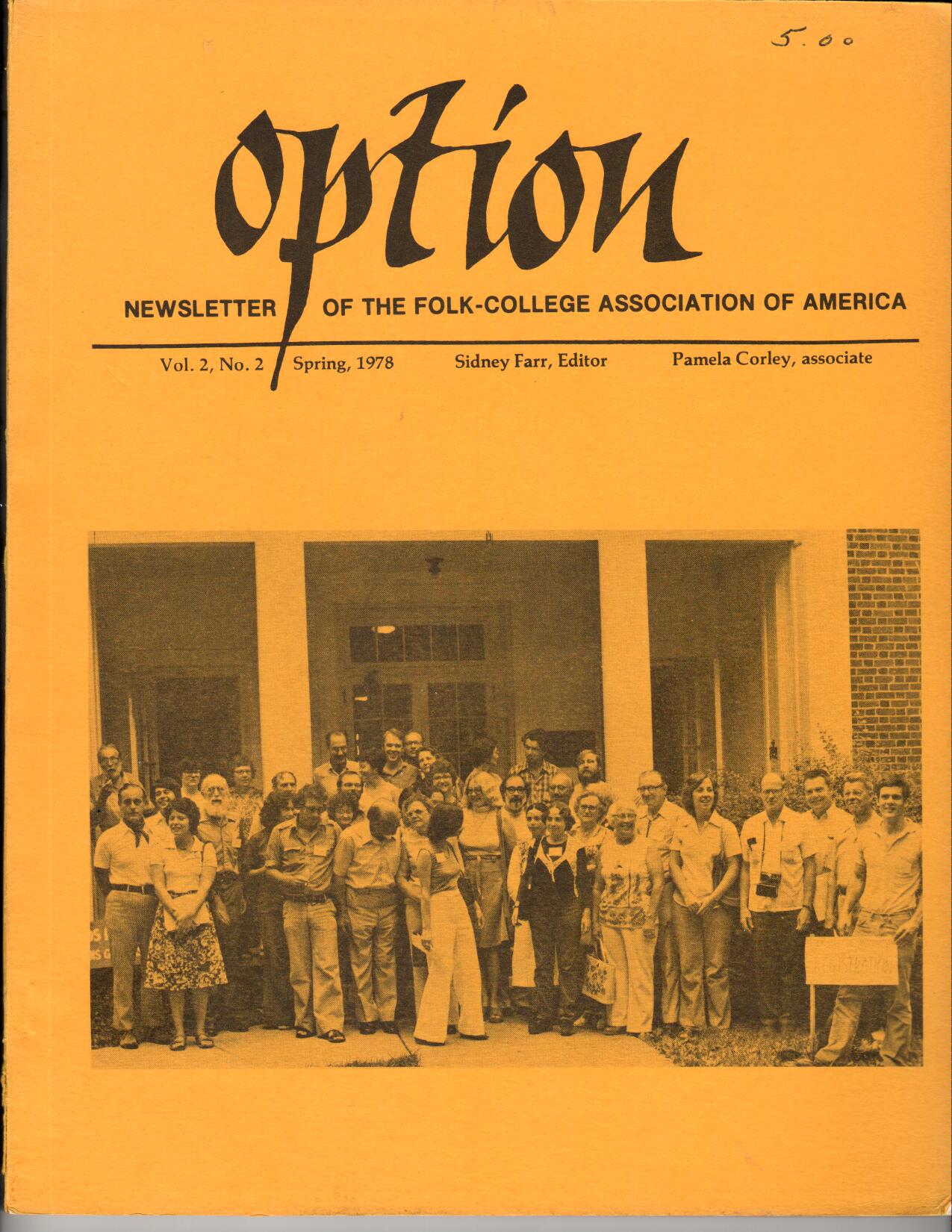

By 1980, the organization incorporated as a non-profit in the state of Kentucky as the Folk School Association of America and had more than 120 members. The organization was holding annual conferences, producing a newsletter, and publishing a Journal called Option.

Until the early 1990s, the organization had begun to shift with new leadership and different perspectives. The name of the organization changed twice, and experienced leadership and financial struggle. Activities of the organization came to a stop in 2002, though now we just like to say the organization went into a hibernation, resting up for the new folk school movement.

Honorary Folk Education Association of America co-founders Kay (Kathryn) Parke (1916 – 2013) and John Ramsay

Honorary Folk Education Association of America co-founders Kay (Kathryn) Parke (1916 – 2013) and John Ramsay The Spring 1978 issue of Option. You can purchase a digital copy on the FEAA’s website.

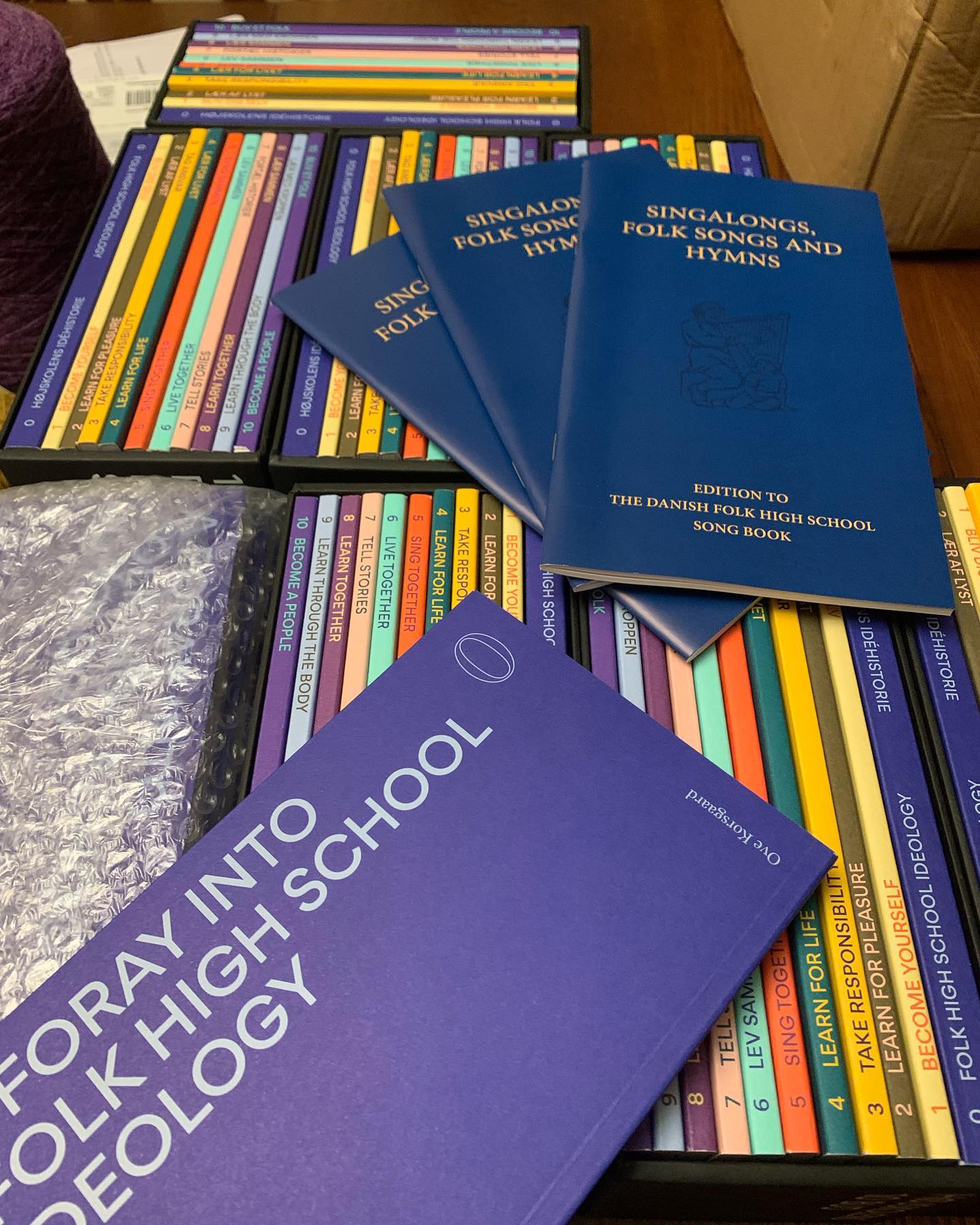

The Spring 1978 issue of Option. You can purchase a digital copy on the FEAA’s website. Books about folk schooling directly from Denmark, also available on their website.

Books about folk schooling directly from Denmark, also available on their website.RG: What kind of work does the Folk Education Association of America do today?

DM: The Folk Education Association of America promotes folk schooling and folk education as a real method and avenue for personal and community development. Our primary vehicle since 2018 has been our Community of Practice and Folk School Alliance project, creating a space for people who are founding and running folk schools to get support from each other and form a common knowledge base. As we see new folk schools pop up, we support these burgeoning entities through coaching, technical assistance, and community building.

The current iteration of the Folk Education Association of America and its project, the Folk School Alliance, began with the energies of a young woman, Kate Parsons. In 2013, she was looking for a place to begin work that would connect people, particularly youth, that conveyed the importance of local schools and unstandardized curricula, ones that meant something to communities. She said to me, “You know, there are certain things a community needs, and so, that’s what schools should be built around, and that’s what students should learn.”

She found herself working for a new folk school, the Driftless Folk School, and through further investigation of folk schools in general, she found contact information for a former board president of the Folk Education Association of America, Chris Spicer. After making that connection, she and a small group of folks decided to hold a meeting at Driftless for like-minded folks interested in the growing number of folk schools in the US/Canada. During this meeting, the group decided to start the Folk School Alliance Project.

RG: The Folk Education Alliance was recently awarded a very exciting research grant from AmeriCorps! Can you tell me about it?

DM: In the next three years, we’ll look at four movements, all in North America––the folk school movement, the African American Craft Initiative, Community Singing, and LifeSchoolHouse Canada, a barter-based form of folk schooling in Canada. We’re going to try to cross pollinate between these families of like movements for community development, economic development, and to strengthen folk education.

We received this funding because communities that tap into their uniqueness of place and the people are often able to capitalize in economic ways and social ways and become healthier communities. So, we’re looking at these movements––these like communities of practice––and bringing them together under the umbrella of folk education to see what happens. If you want to get really academic with it, what we’re doing is called “systems convening.”

We hope that by bringing them together, all of these practices will be elevated, particularly supporting those communities within this grouping that have been marginalized.

RG: Where can people learn more about the Folk Education Association of America? Maybe even get the tools to start a folk school of their own?

DM: You can visit our website at https://www.folkschoolalliance.org/ and follow us on Facebook and Instagram. Our YouTube channel has a number of mini-documentaries tracing the founding stories of some of the folk schools in our network.

You can also become a Folk Education Association of America member or donate on our website. Support from folks all over is essential to fostering existing collaborations and cultivating new ones. Learn more at https://www.folkschoolalliance.org/Join-us

Upcoming Events with Dawn

About Dawn Murphy

Dawn Murphy is a fellow with Fielding Graduate University’s Marie Fielder Center for Democracy, Leadership, and Education and is currently in the final stages of her Ph.D. journey. Dawn’s area of focus combines her work as the facilitator of the Folk School Alliance and her study of transformational learning for social justice. The Folk School Alliance began in 2013 and includes over ninety North American Folk Schools (US and Canada). The group began meeting monthly through an online platform in 2018 and continues today engaging in multiple collaborations supporting and promoting folk schooling in North America.

No Comments