06 Dec Writing About and Living Through Transitional Moments: An Interview with Robert Grand

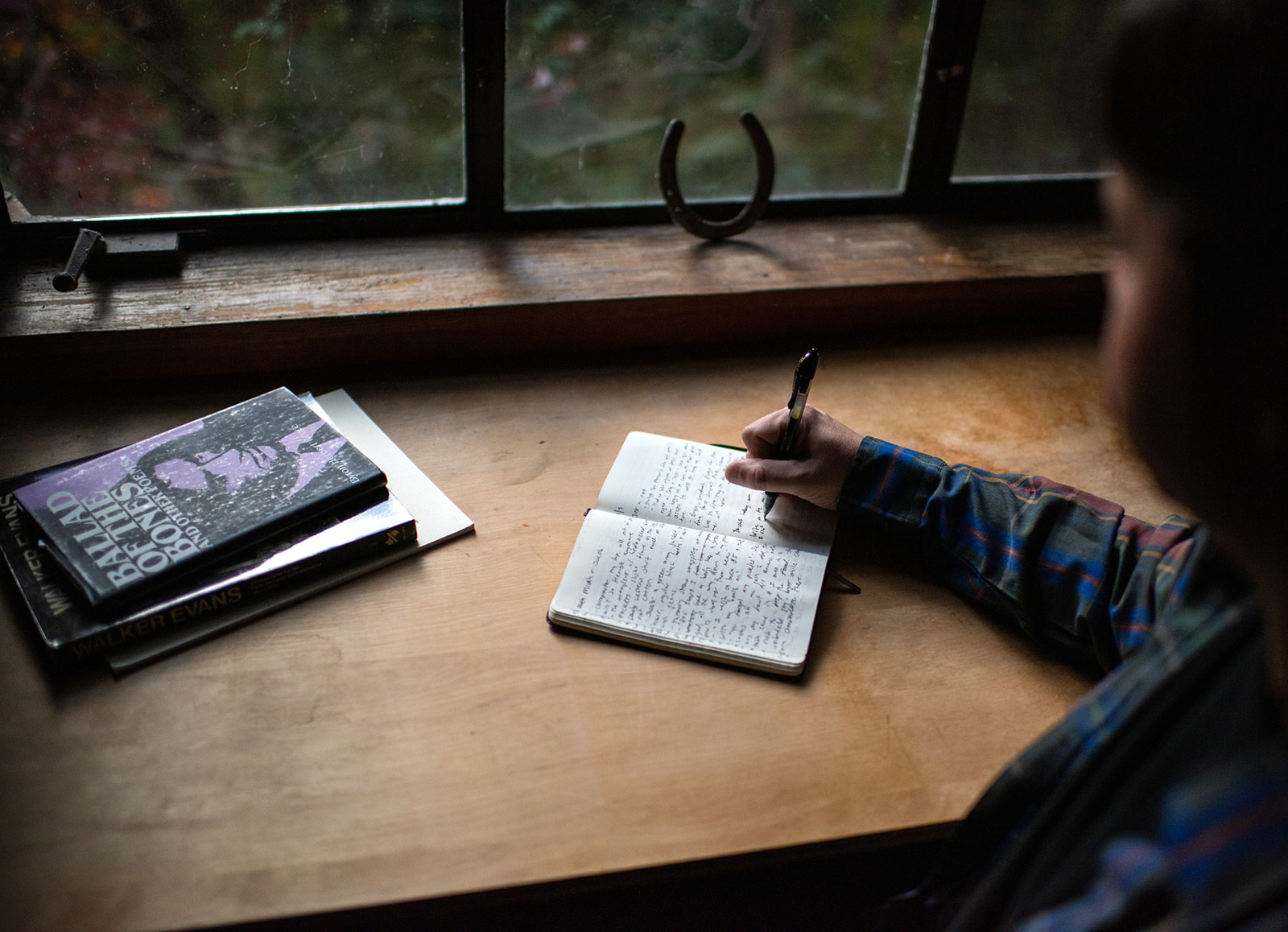

Robert Grand is a writer, photographer, and key piece of our community. He first came in 2019 as a Work Study student and is now our Brand & Communications Manager, working to share how special the John C. Campbell Folk School is with people all over the country. Learn more about Robert in this piece, written in advance of his first time teaching earlier this year. Discover his favorite spots around campus, his writing influences, and how familiar Folk School faces have inspired his craft.

BW: Tell us a little bit about yourself for the folks who may not know you.

RG: I’m Robert Grand, a writer and photographer who’s lucky enough to call Brasstown home. I came to the Folk School for the first time for my cousin Jill’s wedding in 2008. She had moved to the area about five years before and started taking fiddle lessons from Mike Robinson, known to many as a stalwart of our Tuesday and Saturday Night dance bands (and many other campus events, of course). The two fell in love and had their wedding in Keith House–which is not something the school usually does. I remember pulling up in the car with my parents and thinking, what magical Middle-Earth-like village is this?

I went off to college in Nashville, TN and, after graduating, spent the next few years cutting my teeth as a creative in New York City. A decade after my first visit to the Folk School, I came back as a Work Study student, volunteering with the Marketing Department in exchange for class tuition, room, and board.

BW: You’ve been part of the Folk School community in a few different capacities, beginning as a Work Study in 2019 and now being our Marketing & Communications Brand Manager. What made you want to settle down in Brasstown?

RG: When I was a Work Study, I didn’t focus on a particular craft; I dabbled in blacksmithing, cooking, enameling, music, woodturning, and more. The school’s beginner-friendly model and supportive community made me feel like anything was possible.

What impacted me most, and what I gleaned through conversations with students, instructors, and community members, was that many people come to the Folk School for the same reason: to heal.

I heard so many stories over coffee before Morningsong, during weekly Closing Ceremonies, or while sitting together, family-style, in the Dining Hall. We were all curious about craft, of course, but there’s something else about this enchanted valley that attracted us and, in turn, helped us regain our spirit.

I was thrilled to get a full-time job here in early 2021 soon after we reopened. I’ve been working across departments to better express the Folk School experience through articles in our catalog, on our website, and on our social media channels; managing our external communications with media outlets locally and regionally; and solidifying marketing guidelines and language that will help folks around the world better understand the Folk School’s identity, model, and unique place in our country’s educational ecosystem.

BW: How does being part of the Folk School influence your writing/creative practice? What elements inspire you?

RG: Practically speaking, there’s so much to be inspired by here––from the people you meet every week, the familiar faces you see coming back often, and the never-ending list of classes to take and crafts to learn.

The Folk School’s non-competitive ethos and enlightening mission has influenced my creative approach since the day I got here. Digging through the Folk School’s history inspires me greatly––the neighbors who helped build this school and shaped it over the decades, the influential craftspeople who have called the Folk School home at some point, the trials and tribulations that come with surviving almost one hundred years. Our co-founder Olive Dame Campbell was an excellent writer, and her pieces influenced me immensely. Writing about a winter short course in the early years, she said:

“You will remember times in your life when, for a few hours or days perhaps, you were part of a congenial group, a group in which you could freely express that which was hidden deep; when your troubles were for the moment lightened and you could look forward with hope; when you said farewell with quickened pulse and lifted heart. Such have been the inward release and growing impetus of our four folk school months together.”

It’s wild how much of this still rings true today.

BW: What’s your favorite spot on campus?

RG: It’s hard to pick one, but there have been plenty of great memories made at the tables outside the History Center–where a lot of us eat lunch every day. The wooded path between Bidstrup and Keith House also comes to mind immediately. Every time I walk through, I’m taken back to my first day on campus–and I think of how much my life has changed for the better since then.

BW: You’re teaching your first class at the Folk School this January, Renovate Your Story. What excites you most about becoming an instructor?

RG: I’m most excited about experiencing the Folk School from the position of an instructor. I want to foster the nurturing environment we’re known for, less of a “teacher and student” setup and more like friends casually sharing their work with one another and pushing everyone in new directions. The discussions that happen in a writing workshop are like no other, and I’m excited to see what comes out of this weekend.

BW: What can students expect to take away from your class?

RG: My hope is that students learn to see beyond the typical “beginning, middle, and end” story structure. There are so many techniques to play with––for instance, by jumping through time or shifting perspective between characters. A lot of new writers are afraid that the audience will not follow along if they do not move chronologically, but that isn’t often the case. We’ll read a lot of examples too, authors who play with structure in inventive ways like Joan Didion, Danielle Evans, Carter Sickels….the list can go on and on.

BW: What are common themes you like to explore in your writing?

RG: I like to focus on transitional moments––characters moving cross country, reconnecting with people from their past, wrestling with something new they’ve learned about a family member or friend. Two characters being unexpectedly vulnerable with one another, which happens more often in real life than I think we realize. I like to explore everyday mysteries––less of a whodunnitstory and more of a why is this person in the check-out line only buying orange juice, a spider plant, and three pints of ice cream?

BW: We can’t forget, you’re also an incredible photographer! What are the ways writing and photography differ in storytelling, and how do they support one another? Are there particular things you’re drawn to about each medium?

RG: Thank you! For me, photography and writing as crafts are so connected. They truly are two sides of the same coin. They are unique ways to capture a moment or a feeling, each with different layers of context. What’s concealed, or left out of frame, is just as important as what’s revealed. For those familiar with the Folk School, I like to use Olive’s writings and Doris Ulmann’s images as a point of comparison. They both document the same time, and touch on similar themes, but the differences in mood and style, along with the emotions they evoke, are unmistakable. Put together, they offer a dynamic portrait of the school’s early years.

I’m also teaching a photo class in March 2023 as part of our Roots of the Folk School week. We’ll use the school’s 270-acre campus as a photo playground while also touching on regional photo history and processes. We’ll go over the basics––composition, lighting, etc.––in addition to focusing on the techniques and methods of early Folk School photographers like Doris Ulmann and Betty Denash. That class will be a weeklong one, and I’m really looking forward to diving into adventures and new terrain with students that week.

BW: Do you have anything you’ve written/worked on recently that you’re particularly proud of?

RG: In between my time as a Work Study and being a full-time employee–when I was back in New York for a spell–I pitched an article about Richard Carter’s Thursday night Carving Class to notable online magazine The Bitter Southerner. Thanks to their support and immense help, the article turned into a 6,000-word history of the Carvers, titled The House That Carving Built, with Richard’s class as the present-day focal point. It was written in the early days of COVID, when we didn’t know when carving together as we knew it would return. It’s been a few years now, but I’m still very proud of that piece. It definitely helped when I applied for a job here, ha!

Lately, I’ve had the opportunity to review contemporary art and craft exhibitions for national publications Art in America and Artsy. My most recent review for Art in America focused on Cannupa Hanska Luger’s touching show at the Center for Craft in Asheville–the result of years spent trying to recover and reimagine the ceramics practices of his Mandan ancestors.

BW: Do you have any tips for new writers or things you wish you would have known earlier on in your practice?

RG: Get to the point and quickly––in writing and in life! Grabbing someone’s attention is key, and you only have a few sentences (or minutes) to do it. Don’t overthink it. Whatever key fact is most interesting to you will likely be most interesting for your reader.

Early on, I spent too much time trying to set a scene or offer background information when writing or pitching a story. I learned from other writers and colleagues in the media world that this is not always the best approach. Take the Brasstown Carvers article for instance–instead of diving deep into Folk School lore, trying to explain this almost hundred-year-old institution and the carvers’ place in it, I started with, “This incredible humble and kind 70-year-old man teaches a free carving class in a basement once a week. He calls students one by one from the grocery store parking lot to make sure they come and whittle with him.” Now, don’t you want to read more?

About Robert Grand

Robert Grand is a photographer and writer based in Brasstown, NC, where he works as the Folk School’s Communications and Brand Manager. His writings on art and culture have appeared in “Afterimage,” “Art in America,” and “Burnaway,” among others. His feature article about the Brasstown Carvers for online magazine “The Bitter Southerner” was chosen as a Longreads Editors’ Pick. His photographs have been exhibited at the Southeast Center for Photography and included in publications across the region, including “Okra” magazine.

No Comments